Epilepsy, psychosis, or demonic possession? The Case Study of Anneliese Michel.

I wrote this for an essay as part of my MA Medical Anthropology degree: inherent wordcount limitations. There is so much more to say about her story! I hope you enjoy the read nonetheless.

Introduction

The present essay will focus on the case study of Anneliese Michel, a 23-year-old German student who died on July 1st, 1976, after undergoing several Roman Catholic exorcisms and unfruitful medical treatments. Both systems of healing in this case study will be scrutinised and compared in order to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of the events. For this purpose, Lessons Learned: The Anneliese Michel Exorcism: The Implementation of a Safe and Thorough Examination, Determination, and Exorcism of Demonic Possession (2011) by Reverend Bishop John M. Duffey served as contemporary Catholic perspective of the case. The Exorcism of Anneliese Michel (1988) by Felicitas D. Goodman, a cultural anthropologist and linguist focusing on religious ecstatic trance and glossolalia, served as biographical account of the case study, with added cultural and anthropological perspectives. Subsequently, the role and purpose of the concerned episodes will be investigated. In line with symbolic anthropological feminist literature, notably Bourguignon (2004), I posit that Anneliese’ possession trances served as a coping mechanism against her patriarchal environment and the similarly patriarchal systems of healing that failed to ease her ailment. Finally, I discuss her death and how it is understood from both perspectives. I conclude that this case study highlights the disconnect between Biomedicine and religion and displays the radical constructivist nature of our concurrent realities.

Background

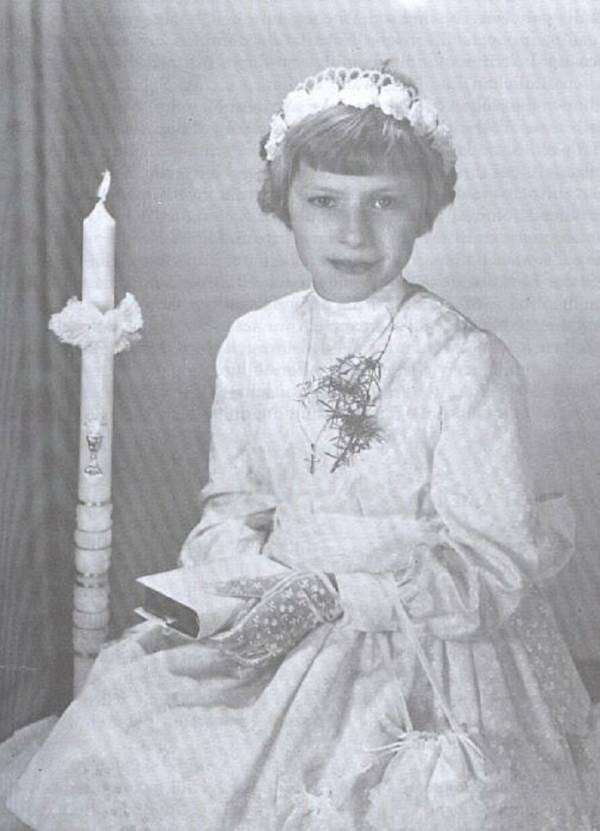

Goodman’s The Exorcism of Anneliese Michel (1988) proved to be the most comprehensive biographical account of the present case; unless otherwise stated, the following information was obtained from this book. Anna Elisabeth “Anneliese'' Michel was born on 21 September 1952 in Leiblfing, Bavaria, West Germany to Josef and Anna Furge Michel. Her father had served in the armed forces of Nazi Germany during WW2, ultimately surrendering to Allied Powers as a Prisoner of War, leaving him “shell-shocked”. Her older sister, Martha, died at age 8 from kidney operation complications, rendering Anneliese the oldest of 4, followed by Roswitha, Gertrud and Barbara. Both parents nurtured a Catholic home environment, discouraging interaction with male peers and attending Mass twice weekly. For the first 15 years of her life, Anneliese was a typical German girl, albeit particularly invested in her academic and religious education.

However, in 1968, she experienced a “blackout”. That same night, she reported having suffered from sleep paralysis and enuresis, but dismissed it as an isolated incident. A year later, after a similar episode, she was referred to neurologist Dr. Siegfried Lüthy for an electroencephalogram (EEG). No anomalies were detected, and the experience was dismissed once more. Shortly thereafter, Anneliese was withdrawn from school and hospitalised for an extended period of time due to physical health ailments including cardiovascular disease and tuberculosis. There, she was bullied by other patients and relied on her faith for moral comfort. Whilst hospitalised, she reported having an ecstatic experience which she attributed to the Virgin Mary. Soon thereafter, Anneliese suffered a third seizure, frightening the other residents who now taunted her by calling her “crazy” and “possessed by the Devil ''.

This episode prompted another EEG, this time administered by Dr. Von Haller, who discovered irregular alpha, delta and theta waves, consistent with generalised tonic-clonic epileptic seizures. She was subsequently prescribed Phenytoin, an anti-seizure treatment. This drug is not prescribed in patients presenting with absence seizures as it has been observed to increase their frequency (Gurbanova et al., 2006). Its potential side effects include gingival enlargement, low blood pressure, tachycardia, cerebellum atrophy, tremors, and several dermatological reactions (Wu & Lim, 2013). Furthermore, it may increase/induce suicidality and psychosis (Rissardo & Caprara, 2020). This treatment did not help Anneliese, who now reported seeing frightening faces while praying, rendering her afraid to participate in religious activity.

Her cardiovascular issues improved and therefore, she was discharged to her family home, only now more irritable and prone to anger outbursts. She ceased her anti-seizure treatment and returned to school in Autumn 1970. Throughout this period, she continued experiencing auditory, visual, and olfactory hallucinations. This prompted further unfruitful investigations. She was prescribed Carbamazepine, another anticonvulsant and Periciazine, an antipsychotic, both with sedating side effects (Pellock, 1987). Despite this, she enrolled at university in fall 1973 and started a romantic relationship. Growing frustrated with the multiple unsuccessful medical treatments, her community sought help from two priests, who both recommended medical rather than pastoral care. A third priest, Father Alt validated the religious hypothesis of Annelise’s symptoms, suggesting she might be more spiritually susceptible to evil influence due to her weak physical state, rather than outright possessed. He prayed for her, and she reported an improvement in her condition. This prompted Father Alt to request authorisation to conduct the formal rite of exorcism to the local Bishop. It was initially denied as her symptoms were deemed not severe enough. Interestingly, The Exorcist film based on the eponymous 1971 novel was released in December 1973

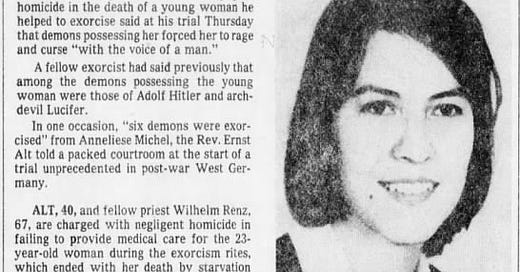

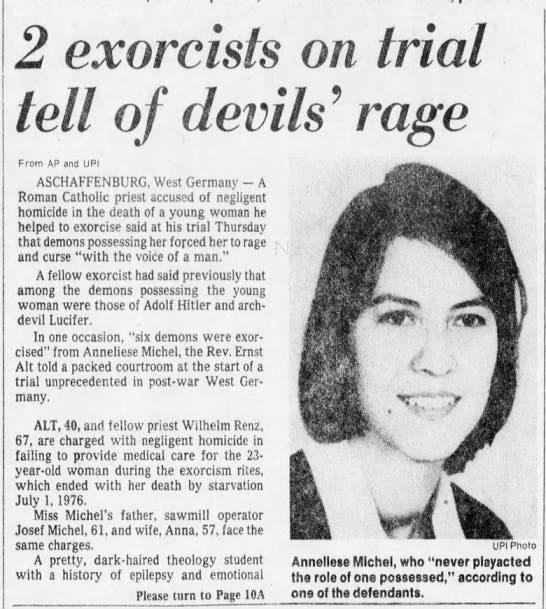

Her symptoms and religious aversion returned acutely in Summer 1975, this time prompting permission to perform the exorcism. Over 60 rites took place from September 1975 to July 1976. The rituals were held on a weekly basis and lasted several hours. Anneliese’s physical state quickly deteriorated, from her repeated genuflections and refusal to eat. She claimed to be possessed by entities such as Cain, Hitler, Nero, Judas, Pastor Fleischmann and Lucifer. As per Anneliese’s wishes, neither her family or pastors sought medical care: it had been overwhelmingly unsuccessful previously and they presumed that she would eventually recover as she had done countless times before. She died a day after her last exorcism, on July 1st, 1976. Medical examiners determined that despite no damage to internal organs, physical exertion alongside malnutrition contributed to her passing, launching an investigation into the matter. The resulting trial focused on attributing responsibility for Anneliese’s death; her parents and the priests were charged with negligent homicide. The defendants argued that she was a lucid adult who refused medical attention in favour of exorcisms; nonconsensual treatment would have been a violation of her dignity. The prosecution argued that had she consulted a medical professional in the week leading up to her death, she would have survived.

Healing

This case study highlights the limits of the Catholic and Biomedical frameworks of healing; despite being seemingly opposite, they both failed Anneliese in similar ways. Both aimed to heal an invisible ailment and relied on external healing agents; either God, or psychotropic medication, administered through their fields’ respective experts, priests or doctors. Ultimately, both systems required Anneliese to surrender her agency to be moved by something beyond her control.

Rather than engaging in religious reductionism Duffey (2013) emphasise that despite their historical struggle, Catholicism and Biomedicine are two different, but equally important approaches to observing divine creation. He further reinforces that it is theologically essential to legitimise Biomedicine, as the Devil and God exist in both the physical and spiritual realm. Ultimately, he blames the priests for Anneliese’s passing; perhaps out of inexperience, they disregarded her physical needs over her spiritual needs, while the battle against the Enemy should have been fought on both fronts.

On the other hand, Goodman (1988) argues that the medicalisation stemming from secularity in modern society is what lead to her death. Possession trance is a recognised phenomenon in Biomedicine but is seldom granted any legitimacy; it is generally understood as a culturally mediated psychotic symptom. Goodman argues that Anneliese experienced a Religious Altered State of Consciousness and that instead, Carbamazepine’s side effects amongst many others, might have affected the oxygen levels in her red blood cells, leading to a suffocation. She blames the materialist nature and coercive tendencies of the Biomedical model of psychiatry for dissuading Anneliese from seeking care; even today, revealing suspected possession to a psychiatrist would most likely result in institutionalisation and forced drugging. Goodman emphasised that Anneliese maintained a great level of insight, displayed in her academic excellence. Faced with this prospect, it seems reasonable that most would opt out of treatment and explore alternatives; to argue against this would be to argue for coercive psychiatric practices.

In Anneliese’s case, medical treatment did not provide an explanation for her affliction, rather, it even seemed to have brought on mood, hallucinatory symptoms and a plethora of numbing side effects. In total, she had suffered five seizures and had not experienced one in years at the time of her death. Duffey warns against religious absolutism at the detriment of physical health, while Goodman posits that hegemonic medicine is ill-suited to help those experiencing complex, layered, spiritual ordeals. Ultimately, pluralistic healing is ineffective when all systems consulted operate under patriarchal hegemony, as discussed below.

Women

The different perspectives on the nature of Anneliese’s ailment and corresponding healing strategies have been outlined, it seems relevant to explore the role/purpose of her episodes. The overrepresentation of women possessed by male entities across societies in possession-trance events appears pertinent in the context of the current case study. Bourguignon (2004) proposed that performing taboo acts as another entity offers women an opportunity to express unconscious feelings that would be otherwise impermissible due to gender expectations. Possession offers an escape from societal subordination and a means to achieve power. She concludes that possession-trance is a psychodynamic coping strategy and response to systemic subjugation; Lewis (1969;1971) conducted ethnographic research in Northern Somaliland and concluded that occurrences of possession by saar spirits were “thinly disguised protest movements directed at the opposite sex” with cathartic ends. Supporting this, Jong (1987) observed male Gods speaking through possessed women in Guinea-Bissau, making political demands such as the cessation of arranged marriage, in turn eroding at the societal patriarchal structures responsible for their oppression.

In the context of the present case study, Duffey (1988) suggests that Anneliese’s cultural and home environment were particularly repressive, leading to a taboo desire to rebel. This desire cultivated an unconscious anger towards her community that could not be acceptably expressed consciously, hence the possession-trance. Primitive, infantile, and unconscious desires can escape repression through equally primitive, culturally mediated symbols (Paul, 1989). Five of the six Alter Egos developed by Anneliese were male profane historical and/or religious figures relevant to her cultural context. Her own Self temporarily abolished, she transformed from a passive object to be cured, to various powerful, decadent male agents. Arguably, the guilt for harbouring these destructive unconscious desires manifested itself through the Cain archetype, the first murderer and first human to experience guilt. Exiled, “the earth no longer yielding her fruits to him” as punishment (Darlington, 2020). Through her 6th Alter-Ego, Lucifer, Anneliese was enabled to embody symbols of ultimate transgression and rebellion from God, which could be interpreted as a supreme act of self determination and emancipation from her repressive worlds (Csordas & Harwood, 1994).

Ritual Death

At the heart of the controversy in this case study is Anneliese’s eventual archetypal “bad death”, or was it? Had she survived, even narrowly, or had her death been easy, resolvable, her story would have probably never gained such notoriety. Her unpredictable, violent and painful death brought no closure and the public has been left wondering for the past 50 years, writing countless books, articles and directing horror films about her demise, trying to make sense of her “unfinished business” (Abramovitch, 2015). Death is often understood as a rite of passage; a transition into the afterlife, rebirth or total annihilation. The ritual is comprised of three stages: separation, liminality and reaggregation (Van Gennep, 2013).

Exorcisms or pharmaceutical regimens, did the healing rituals in this case fail? Who holds the authority to determine ritual failure, participants, or observers? The separation stage in this context can be understood as Anneliese’s extended hospital stays while seeking biomedical healing, or her Ego dissolution during possession-trance episodes while seeking Catholic healing (Bourguignon, 2004). Biomedicine left her in a prolonged state of liminality while waiting for the healing or reaggregation to occur. Liminality is characterised by an unsettling, sometimes painful disruption of the social order, which nevertheless holds great potential for transformation. From a biomedical perspective, the healing ritual failed because Anneliese remained in a permanent “sick” state and reaggregation never occurred. The social order remained disrupted: it would have been resolved had she transitioned into a healthy version of herself.

From a religious perspective, the interpretation is more complex. I argue that reaggregation did occur but not in a hegemonic sense, hence the abject characterisation of this case in popular culture (Creed, 2015; Kristeva, 1982). The ritual performance was completed; however, the debate arises from whether its ritual functions were accomplished. From a modern materialist framework, death, especially in young age, is seen as unfavourable, tragic. From a Catholic perspective, death is merely a transition from the physical realm to Eternal Life; spiritual existence in heaven (Miller, 1993). A few weeks before her passing, she repeatedly discouraged her loved ones from seeking biomedical care, stating that her suffering would come to an end by July (Goodman, 1988). And indeed, she died on July 1st. From her perspective, physical death would only lead her to Eternity with God; an everlasting existence free of suffering.

Conclusion

The case study of Anneliese Michel is unsettling because it highlights a disconnect between two worlds: Biomedicine and religion. It is a display of radical constructivist ideas suggesting a multiplicity of worlds and ontologies that exist concurrently (Henare, A., Holbraad, & Wastell, 2007). Despite those two worlds being seemingly conflicting, I argue that they have similar functions, and both operate from a hegemonic patriarchal framework. The Clinical and Catholic gaze both reinforced the idea of Anneliese as a passive subject to be fixed, rather than as a dynamic agent. Biomedicine, by the repudiation and pathologisation of her lifeworld. Catholicism, by failing to account for the symbolic dimension of her protest against her material reality of subjugation. Susan Whyte (1997) recommends that pragmatic anthropologists consider individuals as “actors trying to alleviate suffering rather than as spectators applying cultural, ritual or religious truth.”. Anneliese explicitly refused to engage with Biomedical healing and sought out exorcisms instead. By inhabiting the space of pain, she arguably achieved radical self-affirmation against both systems that deemed her a passive object (Asad, 2003). Epilepsy, psychosis, or demonic possession; ultimately, our understanding is incomplete but there is freedom to be found in that fact (Haraway, 2020). Anneliese life persists through popular culture, her death birthing myth on how we ought to heal ourselves and others.

References

Abramovitch, H. (2015). Death, anthropology of. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 5, 870-873.

Asad, T. (2003). Formations of the Secular. In Formations of the Secular. Stanford University Press.

Bourguignon, E. (2004). Suffering and healing, subordination and power: Women and possession trance. Ethos, 32(4), 557-574.

Creed, B. (2015). The monstrous-feminine: Film, feminism, psychoanalysis. Routledge.

Csordas, T. J., & Harwood, A. (Eds.). (1994). Embodiment and experience: The existential ground of culture and self (Vol. 2). Cambridge University Press.

Darlington, B. (2020). The Story of Cain: The Myth We Would Like to Forget. Jung Journal, 14(3), 95-106.

Duffey, J. M. (2011). Lessons learned: The Anneliese Michel exorcism: The implementation of a safe and thorough examination, determination, and exorcism of demonic possession. Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Goodman, F. (1988). The Exorcism of Anneliese Michel. Resource Publications

Gurbanova, A. A., Aker, R., Berkman, K., Onat, F. Y., van Rijn, C. M., & van

Haraway, D. (2020). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. In Feminist theory reader (pp. 303-310). Routledge.

Henare, A., Holbraad, M., & Wastell, S. (Eds.). (2007). Thinking through things: theorising artefacts ethnographically. Routledge.

Jong, J. T. V. M. (1987). A descent into African psychiatry. Amsterdam: Royal Tropical Institute.

Kleinman, A. (1980). Patients and healers in the context of culture: An exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry (Vol. 3). Univ of California Press.

Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of horror (Vol. 98). University Presses of California, Columbia and Princeton.

Lewis, I. M. (1969). Spirit possession in northern Somaliland. Spirit mediumship and society in Africa, 188-219.

Lewis, I. M. (1971). Ecstatic religion (p. 23). Pengiun.

Luijtelaar, G. (2006). Effect of systemic and intracortical administration of phenytoin in two genetic models of absence epilepsy. British journal of pharmacology, 148(8), 1076-1082.

Miller, E. (1993). A Roman Catholic view of death. Death and spirituality, 33-49.

Paul, R. A. (1989). Psychoanalytic Anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 18, 177–202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2155890

Pellock, J. M. (1987). Carbamazepine side effects in children and adults. Epilepsia, 28, S64-S70.

Rissardo, J. P., & Caprara, A. L. F. (2020). Phenytoin psychosis. Apollo Medicine, 17(4), 295-295.

Sims, A. C. P. (1988). The psychiatrist as priest. Journal of the Royal Society of Health, 108(5), 160-163.

Van Gennep, A. (2013). The rites of passage. Routledge.

Wu, M. F., & Lim, W. H. (2013). Phenytoin: a guide to therapeutic drug monitoring. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 22(3), 198-202.